Kaiwhakahaere Kerri Nuku and I represented NZNO at meetings in Québec from 27 November – 1 December. We attended a meeting of the Executive Committee of Global Nurses United, and spoke on an international panel hosted by the Québec nurses’ union, FIQ Santé. I spoke first, followed by Kerri, on the topic: “How do your government’s policies affect the care that your members provide and what struggles must you face? What will be your battles over the next few years?” Financial support from FIQ Santé, which enabled our attendance, is greatly appreciated.

Kia ora, koutou.

Greetings, to you all.

It is customary in our young country, when beginning a formal speech at a meeting, to start with an introduction which acknowledges one’s connection to the natural and spiritual world of your birthplace, to a shared experience of migration and to a collective identity based on ancestry. This custom has been adopted from the indigenous culture of the Māori, the tāngata whenua or people of the land.

Nō reira, ko wai ahau?

Ko Kapukataumahaka tōku maunga

Ko Owheo tōku awa

Ko Cornwall tōku waka

Ko te Tāngata Tiriti tōku iwi

Ko Grant Brookes taku ingoa, ā, ko te perehitene ahau ō te Tōpūtanga Tapuhi Kaitaiki ō Aotearoa.

To translate: The sacred mountain overlooking my birthplace is Kapukataumahaka, and the sacred river is Ōwheo. My ancestors arrived on board the ship, Cornwall. My tribe is known as the People of the Treaty, which means I am not indigenous. I reside on the land by right of the 177-year old Treaty of Waitangi between the Māori peoples and the British Crown. My name is Grant Brookes and I am the co-president of the New Zealand Nurses Organisation.

It is then customary to pay respects to the tribe on whose land we are meeting. So I would like to acknowledge that the land on which we gather is the traditional and unceded territory of the Abenaki and Wabenaki Confederacy and the Maliseet.

This biculturalism – embracing the twin perspectives of the of the indigenous and non-indigenous peoples – is today reflected (to a greater or lesser extent) across New Zealand’s health sector. And it is embedded in the structures of our union, as reflected in the two co-presidents you see before you.

It hasn’t always been customary for non-indigenous people to start speeches this way. New Zealand is a colonial settler society. After signing the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, the British Crown and colonists proceeded to ignore it. Māori land, cultural treasures and authority were alienated over following decades through military force and other means. Respect for Māori customs is being restored today through reconciliation for these Treaty breaches.

The initial health impacts of colonisation were devastating. A pre-contact Māori population of up to 150,000 was reduced to 42,000 in little over a century. Our other co-president, Kerri Nuku, will speak shortly about our union’s current battles to improve Māori health status and about government policies affecting the care that our Māori members provide.

Before I turn to the set questions, I would like to briefly explain the structure of the New Zealand health system.

Since 1938, the system has been organised around a core of “socialised medicine”, which resembles the UK National Health Service. The government owns and funds most inpatient and outpatient hospital services, including mental health facilities, and all emergency, intensive care and preventive health services.

Care rationing and waiting lists for non-urgent procedures have become a feature in recent decades, leading to a small private health insurance market. During the period of neoliberal ascendancy in the 1980s and 90s, parts of the public health system – such as elder care and some disability support services – were privatised.

General Practice was excluded from the state-owned system at the outset, and it has largely remained a private business ever since – along with dentistry. Government subsidies, however, fully fund free access for children and part-fund GP visits for adults. Prescription drugs are also subsidised.

Total health spending is 9 percent of GDP. Public spending, generated through general taxes, accounts for 80 percent of this total (Mossialos et. al., 2017).

From this overview it can be seen that government is the ultimate employer of the majority our members and that government policies greatly affect the care that all our members provide.

Two months ago, the New Zealand general election delivered a change of government. Many of the policies of the former conservative government are being reversed. In some cases, where the new Labour-led coalition government has pledged to adopt our policy priorities, we may face struggles to ensure they deliver on their promises in a timely fashion.

Current rapid change means it is difficult to see what our battles may be over the next few years. So I will briefly mention five of the immediate priorities we have raised with the new government.

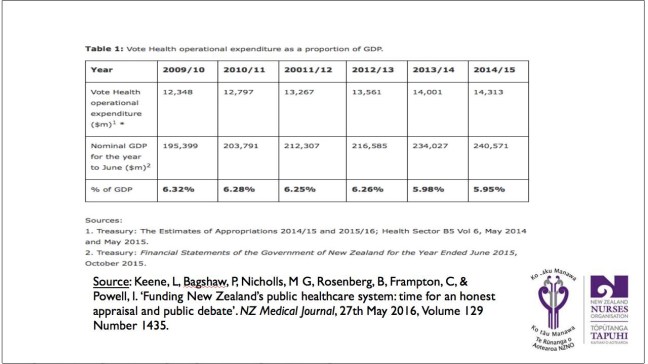

1. Reinstate health funding to levels able to provide the same quality and quantity of health services for our population as at 2009/2010.

Under the previous conservative administration which took office at the end of 2008, government health funding failed to keep pace with population growth and inflation, leading to a cumulative funding shortfall of $1.4 billion. Effectively a 9% cut in operational funding over 8 years, this has meant that our members have been providing care to more people with no corresponding increase in workforce size. The new government has pledged to restore funding. We will battle to make this happen sooner, rather than later.

2. Ensure safe staffing levels and workloads throughout… all health care services

Nurses comprise half of New Zealand’s health workforce. As the largest single group, our members have borne the brunt of the funding cuts of the last 8 years. Unsafe staffing levels, unmanageable workloads and long hours have become the norm in the care our members provide.

We have collaborated in developing a unique local model to ensure safe staffing levels, called Care Capacity Demand Management, as an alternative to legislated ratios used overseas. CCDM relies on a tripartite approach to calculate and adjust staffing levels in the public health system based on patient acuity. Our big battle now is to get this model implemented.

In privatised sectors such as aged care, where a tripartite approach cannot be guaranteed, we will push for mandatory standards for minimum safe staffing levels and skill mix in residential facilities.

3. Full employment for all new nursing graduates

Research shows that employment experience in the first few years post-graduation is a critical factor in retaining nurses in the profession long-term. The New Zealand health system offers a supported Nurse Entry to Practice programmes (NEtP), with enhanced mentoring and educational opportunities. Last year, however, only 62 percent of nursing graduates secured NEtP positions. Many of the others were reduced to voluntary, part time or casual jobs ie. precarious work. We will battle for a NEtP place for every new grad.

4. Fair employment laws

The previous government amended New Zealand’s industrial relations law seven times in 9 years – each time reducing union rights and workers’ rights.

These changes have reinforced structural barriers to fair and balanced employment relationships that, in the rapidly changing labour market, have led to increased job insecurity and persistent low growth in wages, despite growing productivity.

The struggle we will wage, along with the other affiliates of the New Zealand Council of Trade Unions, is not only to roll back these changes – which the new government has agreed to – but to strengthen the pre-existing framework.

5. Health workforce planning

It is projected that half of all nurses will retire over the next 10 to 15 years. An improvement to long term workforce planning is urgently needed to meet projected shortages and to ensure that the workforce is culturally, ethnically and gender representative, enacts Treaty of Waitangi articles, and meets international obligations for ethical recruitment and self-sustainability.

I will now hand over to Kerri to speak more about our struggle for workforce planning – especially to ensure that it is culturally representative of the population.

There are many workforce issues due to funding constraints and I want to focus on one specific area, identify the impact funding constraints has on community and our responsibility as advocates and finally trade agreements

1. Pay inequities

Significant pay disparities of up to approximately 25% exist for nurses working with Primary Health Organisations, especially with Indigenous Health Care services. These disparities occur even in cases where staff have professional qualifications and affect the workforce predominately working within Indigenous service providers who are predominately female.

Pay disparities seem to be the unintended consequence of how the government funds healthcare, which fails to address the differences in infrastructure and investment required specifically within indigenous healthcare service providers versus other larger health providers. This issue affects an indigenous workforce.

These entrenched pay inequities are now affecting the retention and recruitment of nurses in these areas. We will continue to lobby within Aotearoa New Zealand government and raise a complaint to the interventions to the Human Rights Commission and United Nations in New York and challenged the application of our government to ILO Conventions 169 and 149.

2. Community impact

Health funding is imperative to ensure that the we are responsive to the changes in population health needs. Our population (like others) is constantly in a time of change demographics, health demand. However what we have seen is the opposite that is systemic barriers to access health services, escalating social, economic and health disparities has seen an increase in poverty, homelessness and over the years we have seen the emergence of diseases of poverty.

As a union we must ensure that health is central to all government policies and that these policies are integrated to address the global challenges of climate changes antimicrobial resistance and unfair work, trade and immigration patterns.

3. Trade agreements

Achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals, including reducing inequality within and between countries, requires international trade and economic integration agreements to be free of provisions that have the potential to erode government’s rights to act in the best interest of the population and environmental health.

In Aotearoa we promote a coherent system of global health law to further multilateral cooperation in advancing global health equity, by developing and implementing strategies to achieve the sustainability development goals.

We will ensure that no international agreements compromise New Zealand’s ability to control and lower the prices of pharmaceuticals and other medical supplies: to carry out public health programme or maintain and expand the public funding and public provision of health on a non-commercial basis.

To conclude, we cannot estimate that nursing is in a crisis, nurses are overworked and under respected and appreciated. Health is a human right and not a privilege and we have an important role to play in advocacy for our populations. Our challenge as a union is to progress policies, while bringing along the public, to keep alert to the changes in the environment, remain relevant and ensure as a union we continue to engage and grow members in solidarity. Be brave and courageous to take action.

One thought on “‘Struggles we must face’ – Joint NZNO presentation on the Global Nurses United international panel, Québec City”